We’re sometimes asked by other startup founders, potential funders, and our firm, corporate, and legal aid partners why Paladin chose to incorporate as a Public Benefit Corporation, and what that means for the justice ecosystem. We hope this post sheds light on how we at Paladin think about being a social enterprise and contributes to a conversation on how we can work together, leveraging diverse models and offerings, to more effectively bridge the access to justice gap.

The “Why” Behind the Justice Gap

Choosing a model is all about finding the right tool for the job. What job, you might ask? Let’s take a closer look at the justice gap…

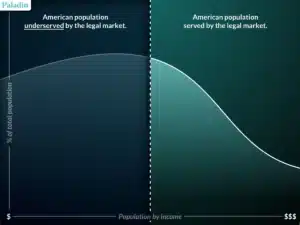

If the legal market functioned perfectly, we wouldn’t have a justice gap on the scale we see today — where the average American lawyer costs >$200 an hour, where at least 60 million Americans (who qualify as low-income at 125% the federal poverty line) are priced out of participating in the justice system, and many millions more are effectively priced out. While there may always be a need for a social safety net to deliver the promise of equal access to justice, unfortunately, the justice gap is so big that it far outpaces the ability to provide a meaningful net.

So, what does this mean? To oversimplify, it means the legal system suffers from a market failure.* (There are many forces that have created the justice gap, but we’ll focus on this for now.)

💡 “Market failure is the economic situation defined by an inefficient distribution of goods and services in the free market. In market failure, the individual incentives for rational behavior do not lead to rational outcomes for the group” — Investopedia

That means the legal services market might look something like this:

There are huge human costs to legal services being distributed so inequitably. And unfortunately, due to scalability and sustainability, most legaltech is also focused on the right side of the line. (That said, there are notable examples like the LSC’s TIG initiative and nonprofits who have been working for years to leverage technology for folks on the left.)

What tools are in our toolkit?

There are a few tools that can help bridge market failures — regulation/government intervention, private sector solutions, public sector solutions, and collective action. For a gap as wide as the justice gap, all four are being leveraged:

- Collective Action. As we’ve all seen, this summer bought unprecedented grassroots action demanding racial justice and criminal justice reform, with nationwide protests on a scale not seen since the Civil Rights Movement. From the NAACP to Black Lives Matter, to new community-led organizations cropping up every day, collective action has arisen as a powerful tool to put pressure on the other sectors to demand justice and drive change. And this doesn’t just apply to criminal justice, since inhumane immigration policies like the immigration ban and child separation have also driven public awareness of the justice gap and its outsized impact on immigrant communities.

- Regulation. There is a growing call to reform legal services to help meet demand in underserved areas (see efforts in Utah and Illinois, for example). One common recommendation is to create a new class of regulated non-lawyer professionals who are authorized to provide certain types of legal services at a more affordable price. California has proposed spurring innovation by allowing non-lawyers to invest in law firms and tech companies, which otherwise would trigger unauthorized practice of law rules (tech companies automating low-level legal issues include LegalZoom and DoNotPay). Right to Counsel — the idea that certain types of civil cases should be treated like criminal matters, with low-income folks receiving guaranteed legal representation — is also picking up steam in New York, where eviction representation is being piloted by organizations like Justfix

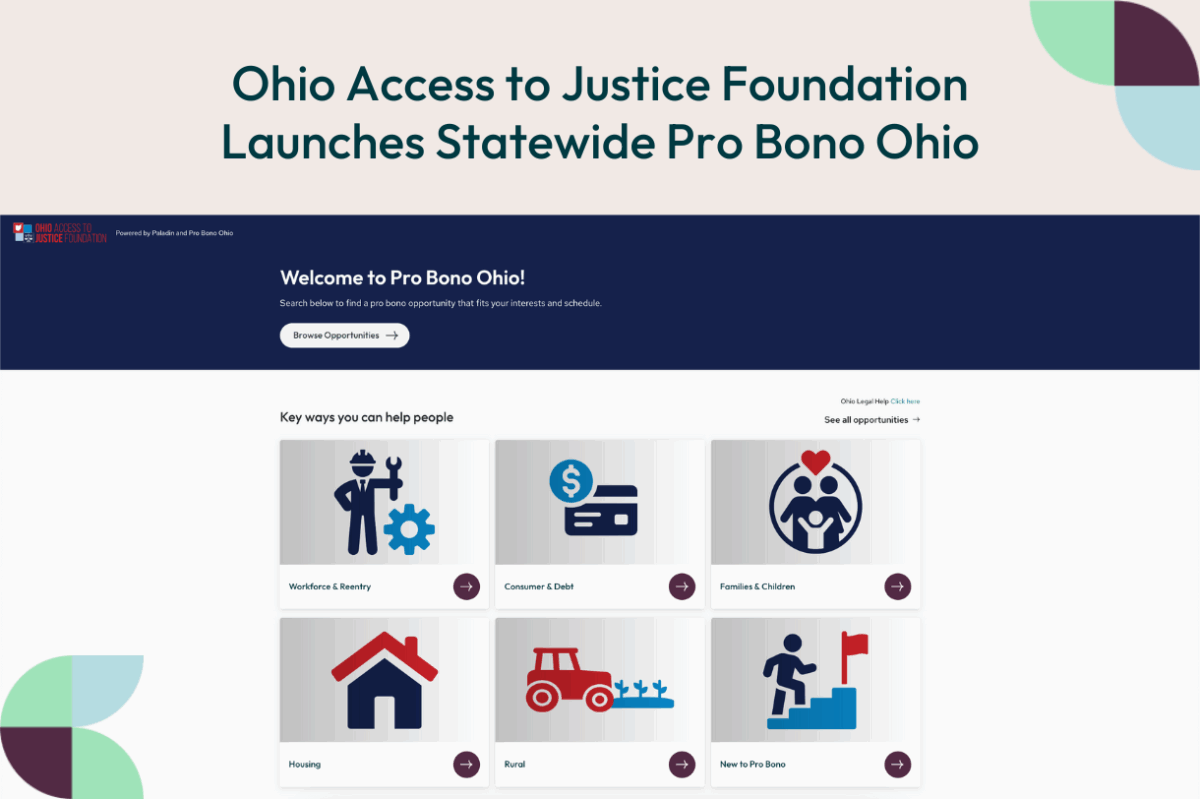

- Public Sector (relevant to pro bono). Legal services organizations and nonprofits serve a fundamental role in A2J toolkit, and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic have stepped up to serve the increased legal need of low-income folks, even in the face of their budgets being threatened. There are now hundreds of legal services organizations across the country with deep expertise focused on serving the specific needs of their communities. LSOs are undergoing a rapid period of innovation since, in the midst of the pandemic, many have adopted remote-friendly processes to keep their clients safe. But even before the pandemic, a number of LSOs have seen success with new models to meet clients where they are — for instance, Legal Hand operates walk-in community centers across New York boroughs, and Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers Foundation runs a program where a lawyer hosts drop-in sessions at local schools to meet with students facing housing issues.

- Private Sector (relevant to pro bono). Lastly — but certainly not least — the private sector has stepped forward as a leader in access to justice, with pro bono programs now flourishing in most major law firms and corporate legal teams across the country, with more added every day. In 2018 firms reported 5M pro bono hours, making up 4% of total billable hours, and 24% significantly expanded their program. In response to the racial justice protests, a coalition of 125 law firms formed the Law Firm Antiracism Alliance aimed at implementing antiracist practices within their organizations as well as leveraging pro bono legal services to promote racial equity in the law. Similarly, a 2018 coalition of law firms called Lawyers for a Sustainable Economy recently reported that they surpassed their initial pledge of $15M pro bono hours, and have successfully donated $24M pro bono hours toward combatting climate change.

- Why a Public Benefit Corporation?

(Pssst… what is a PBC anyway?)

A Public Benefit Corporation is a type of legal entity, separate from a 501(c)(3) or a C-Corporation. It’s a pretty new type of organization, about 5 years old, but it’s caught on quickly — there are now over 5,000 PBCs including household names like Kickstarter, Patagonia, This American Life, and fellow access to justice tech orgs like Community.lawyer.

The PBC is hybrid in that it leverages a for-profit model, but for a public interest purpose. That means that the mission of the company is not solely to pursue social impact or profits — rather, it’s to combine those two into an effective engine for social change.

The Two SS’s — Scalability & Sustainability

We were excited by the growth and potential of the pro bono ecosystem through our own experiences in private sector pro bono, but we still weren’t sure how to structure Paladin. To help us decide, we identified leading challenges that derail achieving access to justice impact.

Time and time again we saw promising initiatives run out of funding, or struggling with securing critical resources. We also heard of geography or issue-area specific initiatives that failed to scale beyond a small subset of potential beneficiaries. (If you’re interested, my Co-Founder Kristen wrote a great piece about these challenges in Legal Executive Institute.)

These top challenges serve as the backbone for Paladin’s model. To anyone working in the field, they’re all too familiar:

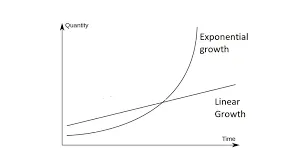

- Scalability — the ability to grow exponentially (as opposed to linearly).

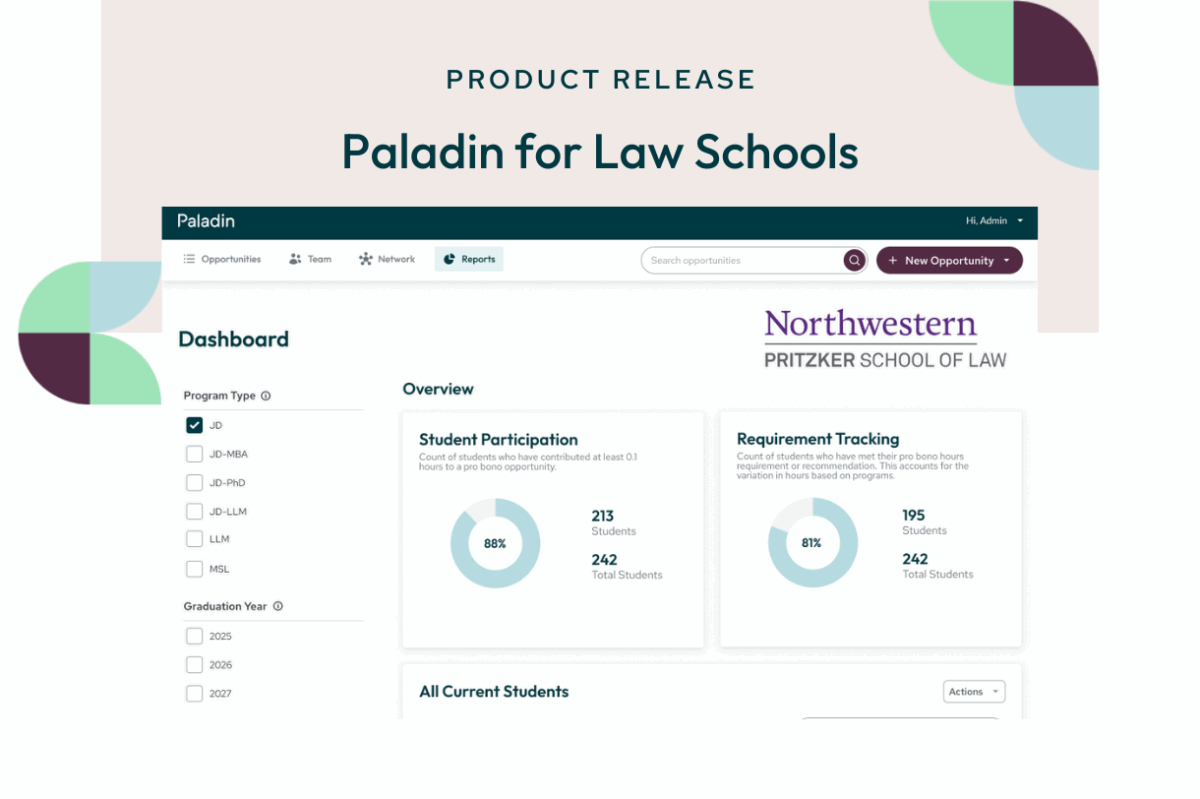

By adopting a tech-driven pro bono network model (where each new LSO, law firm or bar association partner helps exponentially drive the usefulness of our platform) we were excited about Paladin’s scalability, especially because there are common attributes across pro bono issue areas, partner organizations and geographies (even globally). This is relatively unique in law since geography-specific regulations, as well as area-of-law specific challenges, make scalability a rare commodity.

- Sustainability — the ability to operate at a similar level in the future without needing significant ongoing external resources. Of course, sustainability is most reliably achieved from earned revenue, but with low-income people being, well, low income, creating revenue models in access to justice is no easy feat (although not impossible — see UpSolve who leverages an income-generating non-profit model). Furthermore, our ability to generate revenue from organizations that have significant revenue, like AmLaw 250 law firms and Fortune 500s, allow us to build and donate free tools for legal services organizations that are underfunded.

The pro bono space is powered by public interest organizations partnering with the private sector to create both access to justice impact and business value (Kristen also did a great write-up of the business case for pro bono here). Because the private sector is independently motivated to do pro bono — whether it be for altruistic reasons, employee morale, skill-building, brand equity, etc — we realized that Paladin found a rare opportunity to pair profit and purpose by creating tools that help more lawyers do pro bono, and help more clients access the justice they deserve.

Building a “Third Sector” in Law

While we are all familiar with the traditional Non-Profit and For-Profit sectors, PBCs form part of a new “Third Sector” of organizations where those traditional lines are blurred. These organizations view revenue as a powerful means to achieve human and social ends. And since capitalism has repeatedly proven itself to be the most effective engine of human progress ever invented (although imperfect, given the justice gap market failure), the goal of the Third Sector is to harness some of the power of revenue to reinvest and achieve positive impact. There are now thousands of organizations in this Third Sector across every major industry and social issue — from finance to environment, to consumer products and human rights. In law, this Third Sector is just getting started.

Paladin adopted a hybrid profit-meets-purpose model and chose to incorporate as a PBC to contribute to building a Third Sector in law. In doing so, we hope to help co-create a broader movement that breaks down traditional barriers between for-profits and nonprofits, and effectively harnesses the immense power of the for-profit legal services market (currently a $750 Billion market globally) to scalably and sustainably close the justice gap, once and for all.